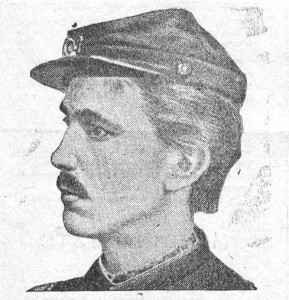

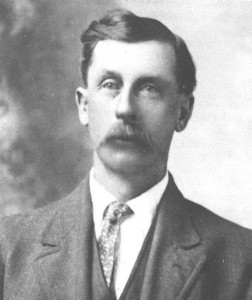

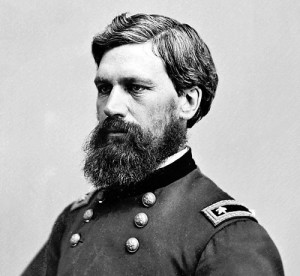

A little more than a week before the Nez Perce arrived at the Big Hole in early August, Colonel (brevet General) John Gibbon could be seen tirelessly preparing his Seventh Infantry troops to depart their headquarters at Fort Shaw in northern Montana and commence the long march to Missoula. Although he occasionally still suffered from a severe left shoulder wound he had received at Gettysburg, the fifty-year-old Gibbon appeared to his soldiers as eager as always on the eve of a campaign. But they also thought there was little chance they would actually fight—their commander, many of the men believed, was simply too cautious.

The previous summer, as his column hesitantly approached the Little Bighorn to join Terry, Custer, and Crook in what the army hoped would be the final crushing blow against the Sioux and Cheyenne, a young, newly-commissioned army surgeon mistook Gibbon’s reluctance for cowardice. “He is trembling & frightened so it is pitiable to see him—If I am to be under the command of such imbecile damned fools I think I’ll get out of it as soon as possible.” But what the surgeon and others did not realize was that Gibbon had reason to believe the number of Sioux and Cheyenne the army faced was much greater than previously thought, numbering possibly in the thousands. Far from a coward, once in battle John Gibbon was the coolest of warriors, as men who had served under him during the Civil War could attest; he was given the affectionate nickname Old War Horse.

After graduating from West Point and fighting in the Mexican War, Gibbon attained the rank of captain and briefly taught artillery at the U.S. Military Academy. Not unlike other regular officers seeking rapid advancement at the outbreak of the Civil War, he accepted a higher rank as a brigadier general of volunteers. Early in the conflict, General George McClellan lauded Gibbon’s “Iron Brigade” as “equal to the best soldiers of any army in the world.” Promoted to brevet major general and in command of a full division, Gibbon suffered a grueling defeat at Fredericksburg, taking some forty percent casualties. At the end of the battle, after being severely wounded in the hand, he purportedly shook his bloody fist at his failed command and shouted, “I’d rather have one regiment of my old brigade than to have this whole damned division.”

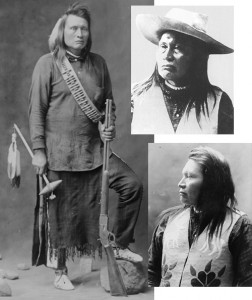

In 1866, the recipient of no less than four brevet promotions, not to mention numerous wounds, he accepted a colonelcy in the regular army. Three years later he found himself commander of the District of Montana under General Terry’s Department of Dakota. One early historian described Gibbon as an example of the army’s old school: dependable, straightforward, not full of “fuss and feathers” as were some contemporaries. Like many frontier officers of reduced rank who had once risen high and commanded much responsibility during the Civil War, Gibbon—sporting a graying Vandyke and at an age considered over the hill for a field officer—was also bright, articulate, and anxious to silence critics who deemed him faint-hearted after last summer’s disaster. Now, learning of the Nez Perce Indians’ “inroad into my district,” he lost no time preparing “to move up the Bitterroot after the Nez Perces & fight them if they will stand.”

On July 28—the same day the bands skirted Fort Fizzle—Gibbon departed Fort Shaw via the Blackfoot River. Seven days later he arrived in Missoula, many of his men having walked the entire 150 miles. The next day, after enlisting Rawn’s command, Gibbon loaded his infantry in commandeered wagons and the column of 15 officers and 146 men struck off after the Nez Perce.

Near Stevensville, the colonel met briefly with Charlot and tried to induce him to supply scouts. But if the chief was willing to help protect valley whites, he was not eager to do the same for the army and he “declined very positively to take sides in the contest.” Gibbon heard from Father Rivalli, who had spent forty years as a Catholic missionary among the Flatheads, that the Nez Perce are “a very dangerous lot” and quickly dispatched a messenger up the Lolo Trail requesting a hundred more cavalry from Howard. He also learned that the bands were armed with as many as 260 guns and were well supplied with ammunition they had bartered from Bitterroot settlers. Dismissing the claim that the Nez Perce had threatened to take whatever they needed had citizens refused, the colonel condemned the settlers’ actions as a “pitiful spectacle.” By furnishing fresh supplies, they had enabled the Nez Perce “to continue their flight and their murderous work.”

There was no evidence of depredations until the command approached Ross Hole, where the men found Myron Lockwood’s ranch “thoroughly gutted.” Now with “sad and revengeful eyes,” Lockwood joined the column. Here Gibbon also received word that the bands had only hours before left Ross Hole and begun the climb toward the Big Hole, but his advance slowed as it encountered difficulties ascending the spur valley, taking “four hours in pulling up the worst hill I ever saw.” Even so, at his present rate of travel, Gibbon knew it was only a matter of time before he eventually caught up. He hoped that the Nez Perce would not discover his presence, claiming that “to surprise them” was absolutely vital. Otherwise he feared they would “either hasten their march, or, what was more probable, turn upon us, and with their superior numbers so cripple us to render any further pursuit out of the question.”

Before they reached Ross Hole, the column was overtaken by several late-arriving cavalrymen along with two companies of thirty-five volunteers, led by “Captains” John Humble and John Catlin. Both men later claimed that although they were personally opposed to pursuing the fleeing bands, their men had insisted. Humble recalled that Gibbon “appeared rather surly,” doubting their worth as soldiers. By Ross Hole, however, the colonel asked Humble to take his men, scout ahead and engage and halt the Indians until his command could catch up. Humble refused; it was too risky. Then Gibbon tried to embarrass the volunteer by exposing his reluctance in front of his men, prompting Myron Lockwood to step forward, demanding to “‘see the color of the feller’s hair’ that refused to go. I said, ‘Mr. Lockwood, you better look at mine! I am the man! If you get into a scrap with those Indians you will know that you have been somewhere!’” With those prophetic words, Humble mounted his horse and announcing that he “was not out fighting women and children,” rode off toward home alone.

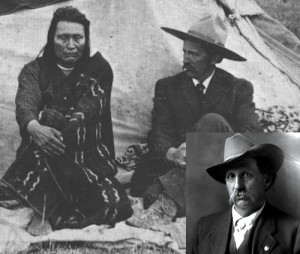

The Nez Perce camp along the Big Hole River, looking back on the hillside where Gibbon discovered their camp.

As the command went into camp at the foot of the pass leading to the Big Hole on the evening of August 7, Gibbon sent Lieutenant James H. Bradley and some sixty mounted men, including John Catlin’s volunteers, to scout ahead and locate the Indian camp. Ascending the ridge in the dark, the men encountered so much fallen timber that it was daylight before they managed to work their way down to the open basin of the Big Hole River. Bradley suspected he had found the camp when scouts reported that a few miles ahead they had heard sounds of voices and the chopping of wood. Taking two men along, the lieutenant cautiously advanced, climbing a tree to get a better view when he reached the last of the timber. Spread before him in the meadow at the foot of the mountain was the Nez Perce camp.

The men immediately returned to the others, dispatched a messenger to Gibbon and prepared to remain hidden until the remainder of the command arrived. In the note he sent Gibbon, Bradley admitted that the Indians “have seen my camp, but I do not expect them to attack me.” Some Nez Perce later acknowledged they observed white men on the hillside that day, but thought little of it. Since traveling through the Bitterroot, whites had been watching their movements and they had grown accustomed to the followers. They were confident Bitterroot settlers had been mollified by their pledge of nonviolence in return for safe passage. As for the army, they believed General Howard was still in Idaho.

By one o’clock that afternoon, using draglines to assist the wagons up the rough road to the pass, Gibbon’s column crested the ridge and began the descent down Trail Creek, following the route Bradley had taken only hours before. Arriving at the scouts’ camp about sundown, and no doubt with the army’s favorite method of assault in mind, Gibbon ordered a surprise dawn attack. Each man was given two days’ rations, ninety rounds of ammunition, and a cold supper of hardtack and raw salt pork since fires were forbidden. Then they lay down to sleep. But “to sleep, one’s mind must be at rest, and mine was very far from it,” Gibbon said, unable to shake the belief that the Nez Perce were aware of his movements and were preparing a trap.

At 11 P.M., the command was awakened. Some twenty men stayed behind to guard the wagons, and another squad was ordered to follow with the howitzer and two thousand rounds of rifle ammunition at daybreak. Then Gibbon set off with 149 soldiers and 35 volunteers toward the Indian camp four or five miles away. With no moon and only starlight to guide them, the column noisily stumbled over rocks and fallen timber. About 1 A.M., the men rounded the shoulder of a slope and saw campfires and the outline of tipis at the edge of the meadow below, just beyond where a bench of small lodgepole pines jutted away from the hillside. As the command worked their way down to the trees, Gibbon was suddenly startled when he saw “moving bodies directly in our path on the sidehill”; he realized they had come upon the Indian horse herd. There were several anxious moments when the horses began to neigh and whinny, and dogs in the camp began barking. Soon the remuda moved away up the hillside and the dogs quieted. In the dim starlight, Gibbon could make out the Big Hole River, only a waist-deep creek this high in the valley, meandering between the bottom of the slope and the camp, with the marshy ground between covered with scattered willows.

The men awaited daybreak, shivering in the cold morning air, only a couple hundred yards away from the village. Lieutenant Charles A. Woodruff, the colonel’s adjutant, recalled distinctly hearing the occasional bark of a dog, the “cry of a wakeful child, and the gentle crooning of its mother as she hushed it to sleep.” Suddenly a soldier struck a match to light his pipe, echoing a similar thoughtless action at White Bird Canyon two months earlier. Although Gibbon said later the man deserved to be either “shot on the spot or knocked over with the butt of a musket,” an officer quickly extinguished the light and the incident passed undetected. Reflecting on his good fortune to be precisely in the position he desired, Gibbon began worrying about the horse herd, believing it was critical to run off the horses and set the camp afoot. When he told his scout, H. S. Bostwick, to take some men and quietly drive the herd back along the trail, Bostwick—“who had spent all his life among the Indians”—assured Gibbon that the Nez Perce “would never allow the herd to remain unguarded” and that to try to drive them away would certainly “create alarm and render a surprise impossible.” Later, when it became obvious the horses had not been guarded, Gibbon would regret his decision, saying if he had gone after the herd Bostwick’s life would have been saved.

Just before first light, the scout turned to Gibbon and whispered, “If we are not discovered, you will see the fires in the tipis start up just before daylight, as the squaws pile on the wood.” Not long after, “the sky in the east began to brighten, the fires began to blaze all through the camp,” and Gibbon deployed his men along the bottom of the hill. Soon came whispered orders to begin moving quietly through the brush across the creek bottom toward the camp. When the men heard the first shot, they were to fire three volleys and “charge the camp with the whole line.”

Dawn came early that morning for a Nez Perce man nearly blind with old age. Mounting his horse and riding through the camp on his way across the creek in search of the horse herd, he passed women beginning to kindle cooking fires. Some were uncovering small pits where overnight they had buried camas roots in the traditional manner of baking with hot rocks or coals. Nearby lay green lodge poles, freshly cut, peeled and drying; others supported the eighty-nine tipis that stretched up and down the open ground along the creek.

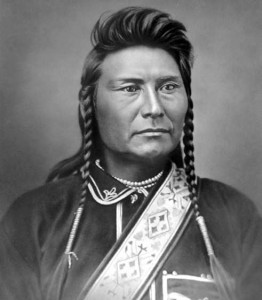

As the herder rode through camp, there were few people awake. The day before there had been an argument when the tewat Pile of Clouds had purportedly warned Looking Glass, saying, “Death is behind us; we must hurry; there is no time to cut lodge poles or hunt!” So much were this man’s premonitions valued that some wanted to move immediately. But the bands had been living in brush shelters since their rout at the Clearwater, and the Big Hole was one of the last locations to cut prime poles before heading east. The chief apparently was determined they not arrive in Crow country appearing as paupers. Others suggested sending scouts to watch over the back trail. Several theories have been advanced on why Looking Glass did not encourage this endeavor, which in retrospect appears only prudent. He may have feared more depredations if he allowed warriors to return to the settlements, or he may have felt confident that since whites had offered no resistance, they tacitly approved of the Indians’ intentions. Some of his people later accused him of simple stubbornness and arrogance in flaunting his ascendancy over the other headmen. At any rate, the warriors needed fresh horses for scouting and they had been unable to convince an older, wealthy warrior to provide the required mounts. Instead the camp had spent the night running foot races, dancing, and celebrating their successful journey through the Bitterroot.

The horse herder crossed the creek near the north end of camp and began riding through the willows. About halfway to the hillside, he stopped, leaned forward on his horse, and attempted to make out in the dim light what was before him. Three or four volunteers suddenly stood up and fired, killing the man instantly. Up and down the line, the men fired three salvos and, yelling at the top of their lungs, charged through the remaining willows toward the camp.

The surprise was sudden and complete.

The closest troops rushed the center of camp, spreading out as men, women, and children stumbled half asleep from their tipis, most having difficulty comprehending what was happening. As “squaws yelled, children screamed, dogs barked, horses neighed, snorted, and many of them broke their fetters and fled,” recalled an early chronicler of the attack, warriors “usually so stoical [ran] wild and panic-stricken like the rest,” too badly frightened to use their weapons. Almost at once, the fighting became hand-to-hand. One soldier reported bewildered warriors running away a short distance, then rushing back to their tipis for weapons; many shot at such close range that their flesh was burned by the powder from the blast.

Entering the camp, Lieutenant Woodruff saw tipis “suddenly light up,” shadowy figures momentarily silhouetted as soldiers stepped inside and fired at the occupants, many still under buffalo robes. Before long “the ground [was] covered with the dead and dying, the morning air laden with smoke and riven by cheers, savage yells, shrieks, curses, groans. No one asks or expects mercy—our only commands are: ‘Give it to ’em, push ’em, push ’em!’” Later Woodruff stated that Gibbon’s plan was to force the Nez Perce out into the open grassland and separate them from their weapons and horses. Beyond that there was no plan. More than one account claims that Gibbon unofficially told his men that “we don’t want any prisoners.”

When the shooting began, six-year-old Josiah Red Wolf’s father covered his son with blankets and told him not to move. “I had no intention of leaving,” he said, “but my mother started out of the tipi with my sister on her back. She was shot and my little sister shot right there in the tent and both were killed. . . . I was very frightened as sound of guns and screams of wounded increased. . . but I never moved.”

Chief Joseph’s ten-year-old nephew Suhm-Keen was asleep under a buffalo robe next to his grandmother Chee-Nah in a tipi at the southern end of the camp. “Suddenly a rifle shot, then neighing of startled horses roused us. Chee-Nah rose to peer out and a bullet pierced her left shoulder . . . blood streamed from the wound as she pushed me from the tipi crying, ‘Suhm-Keen run to the trees and hide!’ I raced up the slope as fast as I could . . . bullets kept whizzing past clipping off leaves and branches all around me. I was very afraid. . . . Soon some other boys joined me there and we watched trembling at the awful sight below.”

Emerging from his lodge unarmed, Wounded Head—who had spared Isabella Benedict during the White Bird battle—was shot point blank in the head, the bullet deflecting off his skull after piercing hair rolled into a tight ball on his forehead. He fell, momentarily stunned, unable to move. As he watched, his two-year-old child crawled from the tipi and began toddling toward some soldiers. His wife ran after the child but before she reached it, a soldier raised his rifle and shot it through the hip. Picking up the child, she turned to flee and was shot in the lower back, the bullet coming out near her breast. Like several other warriors who managed to escape being killed or wounded in those first minutes, when he recovered, Wounded Head stopped fighting long enough to remove his injured family to safety. Although his wife survived, the child died four days later.

Chief White Bird’s nephew, who subsequently took the chief’s name and was then about ten years old, woke up when the shooting started. His mother grasped his hand, and once outside their lodge, they began running toward the only available protection: the scattered willows the troops had just charged through. As they ran, a bullet cleanly took off her middle finger and end of her thumb, also severing her child’s thumb. Reaching the shallow creek, the woman and boy jumped in, squatting down in the cold water with only their heads above the surface. Soon several other women and children joined them huddled in the creek, White Bird recalling that “one little girl was shot through the under part of her upper arm. She held the arm up from the cold water, it hurt so. It was a big bullet hole. I could see through it.”

Nearby on shore, a woman shot through the left breast “pitched into the water and I saw her struggling. She floated by us and mother caught and drew the body to her. She placed the dying woman’s head on a sandbar just out of the water. She was soon dead. A fine-looking woman, and I remember the blood coloring the water.” Suddenly soldiers appeared on the bank. One pointed and they all began aiming at the women and children in the creek. “Mother ducked my head under water. When I raised out, I saw her hand up. She called out, ‘Women! Only women!’ When mother called those words, the order must have been given those soldiers to quit. They brought their guns back, and turned the other way.”

Young White Bird and his companions were fortunate. From most accounts, it appears soldiers made little distinction between men and the camp’s women and children. There were exceptions, such as when a small girl saw a soldier pick up a baby lying beside its dead mother and hand it to another woman who was wounded, and again when an officer stopped his men from killing two women. But by and large, the greatest number of victims in those first minutes were women and children. Nez Perce claimed a soldier entered one lodge and killed five children attempting to hide under a buffalo robe. Corporal Charles Loynes of I Company recalled seeing a young woman with a baby “lying dead with the baby on her breast, crying as it swung its little arm back and forth—the lifeless hand flapping at the wrist broken by a bullet.” Not far away a woman who had given birth the night before was killed in a tipi along with another woman serving as her nurse, still holding the baby in her arms. “It’s head was smashed,” said Yellow Wolf, “as by a gun breech or boot heel.”

Gibbon would say later that in the poor morning light, identification was difficult and thus the killing of women and children was “unavoidable.” When tipis were broken into, “squaws and boys from within fired on the men, and were of course fired on in turn.” Doubtless this was sometimes true, considering the nature of the attack, particularly for those who refused to accept a passive death.

Wounded Head recalled seeing one woman charged by a soldier with a bayonet on his rifle, seize the gun, wrest it from him, and throw him to the ground. The man jumped up but was shot and killed by a nearby warrior.

At least one soldier, Private Charles Alberts, entered a tipi only to find himself surrounded by women and children coming at him with knives and hatchets. Grasping the barrel of his rifle, the private “dealt blows fast and vigorous, right and left,” until he managed to fight his way back outside. Private George Lehr was struck in the head by a glancing bullet and knocked unconscious. Recovering, he realized a woman was dragging him by the heel, an action that ceased when he “secured a rifle and dispatched her.”

Gibbon’s further claim that “the poor terrified and inoffensive women and children crouching in the brush were in no way disturbed,” appears less accurate. Later he would say that when women begged for mercy and held their babies out to him, “it touched his heart” enough to spare them. With few exceptions, such protection has been emphatically denied by Indian as well as some white survivors.

Eelahweemah (About Asleep), a child of fourteen, hid in the creek with his younger brother and five women and watched as all the women, including his mother, were killed by soldiers shooting at them from shore. As the women fell one by one, the two boys scrambled out of the water and escaped. That the creek offered scant protection was echoed by Corporal Loynes, who witnessed several women throw a buffalo robe into the water, then submerge themselves beneath it. But they had to have air, so where the buffalo hide was slightly raised, said Loynes, “a bullet at that spot would be sufficient for the body to float down the stream.”

Others tried hiding in willows along the bank. One woman lay down with her arm around a young girl. “Bullets cut twigs down on us like rain. The little girl was killed. Killed under my arm,” recalled the woman in disbelief many years afterward, as if the horror of what had happened was still unthinkable. Decades later when historian Lucullus Virgil McWhorter began collecting Nez Perce accounts of the battle, often those who were children at the time were the only witnesses willing to relate their stories, many of the older people finding it still too painful to speak. Returning to the Big Hole with McWhorter some fifty years after the war, Yellow Wolf was frequently overcome with both anger and grief, able to account for the deaths of women and children only because “some soldiers acted with crazy minds.”

During those first few minutes of attack, a brief defense started when twenty warriors took cover behind some willows and began shooting into the charging troops near the center of the camp. Corporal Loynes was wading the creek when a fellow soldier a few feet away suddenly “leaped into the air giving the most awful yell and dropped dead.”

Leading the initial attack on the right or southern flank, the soldiers of Company A had a somewhat longer distance to travel than others, arriving just in time to catch the Nez Perce defenders from behind. The company captain, William Logan—described as an Irishman with “much of the rollicking humor and warm geniality of his race” and who had played a role in the Fort Fizzle affair—was three years away from retirement and still “suffering the recent death” of both his daughter and granddaughter (the wife and child of another officer in the battle). Now as Logan led the charge into the camp, warriors turned and fired, killing him instantly.

Rainbow, considered by many in the bands as their greatest warrior, was one of the first to die, shot through the heart. At least one warrior—Wounded Head—was so shocked by his death that he lost the will to fight, making his way to the yet unattacked northern part of the camp. Two Moons recalled that Rainbow had told him, “I have the promise given that in any battle I engage in after the sunrise, I shall not be killed. I can therefore walk among my enemies. I can face the point of the gun. My body no thicker than a hair, the enemies can never hit me, but if I have any battle or fighting before the sunrise, I shall be killed.”

Such belief—along with a taboo that served as an explanation should it fail—was not unusual among warriors, although it was often met with derision from whites anxious to demonstrate its fallibility. No doubt, an unshakable belief in their own invincibility gave warriors a fearlessness their enemies found intimidating, thus enhancing their chances of survival—and perpetuation of the belief—in battle, where fear itself is often the greatest killer. Beyond that, such stories are difficult for non-Indian minds to cogently explain. Yellow Wolf, whose entire account of the war resonates with such forthright and uninhibited candor, is not easily dismissed when he relates the story of a “very old man” who sat outside of his tipi throughout the battle smoking a pipe.

He was shot many times! As he sat on his buffalo robe, one soldier shot him. He did not get up. Others shot him. Still he sat there. Others shot him. He did not move. Just sat there smoking as if only raindrops struck him! Must have been twenty bullets entered his body. He did not feel the shots! After the battle, he rode horseback out from there. He grew well, but died of sickness in the Eeikish Pah [Indian Territory] where he was sent after the surrender. The wounds did not seem to grow. It was just as you see mist, see fog coming out from rain. We saw it like smoke [steam] from boiling water, coming out of his wounded body.

Another warrior dying early was Wahlitits, one of the original young trio whose violence precipitated the war. He and his pregnant wife took refuge in a small depression near the creek. According to a relative, when the soldiers drew close Wahlitits told his wife to flee. As she rose to go, a bullet slammed into her shoulder, knocking her down. Wahlitits killed one of the soldiers just before another shot the warrior through the chin, killing him instantly. Struggling to aim her husband’s rifle, the woman managed to shoot the soldier but others quickly returned the fire, a bullet entering her throat, passing down her spine and exiting near her lower back. Found after the battle, Yellow Wolf said she was “lying across her husband’s body as if protecting him.”

Twenty minutes into the battle, soldiers had gained control of the southern end of the village, consisting mostly of the bands of Joseph, White Bird, and Poker Joe. Those who escaped made their way toward the camp’s north end. One was Seeskoomkee, the limbless ex-slave who had warned of the soldiers’ approach at the White Bird Canyon battle, observed alternately rolling and hobbling on his one hand and knees until he gained a shallow depression at the edge of camp. Also seen was Joseph, carrying his two-month-old daughter, who once again had managed to escape from soldiers at the seemingly last possible moment.

Confident the Nez Perce were demoralized and near defeat, Gibbon now made a blunder, ordering his men to stop pursuing them, sweep the nearby willows for survivors, and torch the camp. Soldiers began setting fire to several tipis, but the morning dew had dampened the skins and with the lodge poles still green, the men succeeded in burning only eight tipis. One woman, Owyeen (Wounded), later recalled that children who had avoided detection earlier by hiding under buffalo robes in one of the lodges began screaming when their tipi went up in flames.

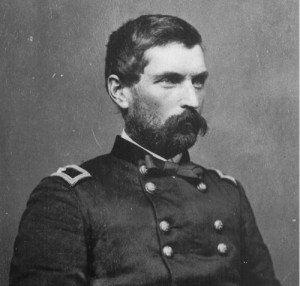

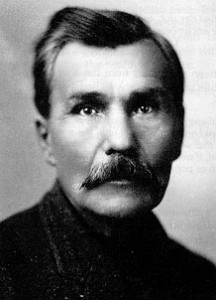

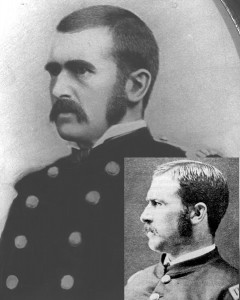

Soon Gibbon learned that the attack on the northern part of the village (his left line) had failed when Lieutenant James Bradley had fallen early in the charge, shot through the heart. Without a leader, the men had simply drifted back toward the center of the line, leaving that part of the camp unchallenged.

Lieutenant James Bradley only the year before at the Little Bighorn had rescued Reno and Benteen’s troops after Custer’s fatal battle.

When Gibbon failed to press his advantage, White Bird and Looking Glass began exhorting the survivors, their loud voices heard even by soldiers at the far end of the camp. One warrior recalled that White Bird was enraged, shouting, “Why are we retreating? Since the world was made brave men fight for their women and children. Are we going to run to the mountains and let the whites kill our women and children before our eyes? It is better we should be killed fighting. Now is our time. Fight!”

For warriors who had the desire, the difficulty was finding weapons. When the battle started, Yellow Wolf had been sleeping unarmed in a tipi in the northern part of the camp. At the first shots he ran toward the fighting, unsuccessfully imploring several returning wounded warriors to give him their weapons. Finally he saw a injured soldier “crawling like a drunken man.” He clubbed the man with his kopluts and took his gun. “I saw teeth loose in his mouth, and easily took them out. I had never seen such teeth,” recalled the startled warrior. Following Yellow Wolf’s example, or using their own or borrowed weapons, some thirty or forty warriors began attacking the soldiers with telling accuracy. At almost every crack of a rifle,” said Gibbon, “some member of the command was sure to fall.”

Spurring his horse across the creek toward the camp, Gibbon dismounted, realizing that in the withering fire of the counterattack, “horseback was not the healthiest position to be maintained.” As the colonel watched the fight, a fellow officer remarked that Gibbon’s horse’s leg had been broken by a bullet. Only then did Gibbon realize that “the same bullet which broke my horse’s leg passed through mine” as well. The colonel promptly sat down on the bank and began washing his wounded thigh. As the Nez Perce approached, Gibbon saw several warriors moving to cut off his line of escape back toward the hillside. With bullets coming “from all directions,” and finding his position “untenable” and sure to result in “increased losses,” Gibbon called a retreat.

Encouraged by the soldiers’ withdrawal, the warriors quickly charged. Grizzly Bear Youth remembered one particularly “tall, ugly looking man” who, suddenly turning around and cursing, “made for me,” swinging his gun by the barrel and attempting “to strike me over the head with the butt end. I did the same thing. We both struck and each received a blow on the head. The volunteer’s gun put a brand on my forehead that will be seen as long as I live. My blow on his head made him fall on his back. I jumped on him and tried to hold him down. The volunteer was a powerful man. He turned me over and got on top. He got his hand on my throat and commenced choking me. I was almost gone and had just strength left to make signs to a warrior, who was coming up, to shoot him. This was Red Owl’s son, who ran up, put his needle gun to the volunteer’s side and fired. The ball passed through him and killed him. But I had my arm around the waist of the man when the shot was fired, and the ball after going through the volunteer broke my arm.”

The retreat became a rout when the soldiers crossed open ground and, in the intense crossfire, left their wounded to make their way as best they could. When volunteer Tom Sherrill jumped into the creek and began wading across, he was startled to see a white girl about sixteen years old cowering in the waist-deep water. No one else remembered her during the battle, although an unknown young woman of light complexion had been reported traveling with the bands as they passed through the Bitterroot Valley.

Approaching the hillside, a young corporal cried out, “To the top of the hill—to the top of the hill, or we’re lost!” Writing later that “the top of the hill was the last place I wanted to go or could go,” a limping Gibbon reminded the man amid a few nervous chuckles from soldiers within earshot “that the commanding officer was still alive,” and ordered the men to the nearby timbered bench.

Here on about an acre of ground, the command dug in behind pine trees some three or four inches in diameter—trees, Gibbon remarked, that now appeared unusually “large” considering the circumstances. With Nez Perce snipers in trees on the hillside above them, the men frantically dug rifle pits with their trowel-shaped bayonets—large, unwieldy instruments soon to be discarded by the army (although Gibbon credited them with saving his force from annihilation). Others used tin cups, knives, and even an empty canteen split in half to scoop and dig. Corporal Loynes recalled that one man would scrape up the dirt while every second man continued to fire. Those lucky enough to drop behind logs and stumps, said Gibbon, were “millionaires (for the time being) in safety.” For volunteer Luther Johnson, this particular wooded spot was intimately familiar. In the 1860s, he had prospected the area for gold but had found nothing. Now Johnson and another volunteer fought for their lives from the very prospect hole he had dug years earlier.

As the men prepared for the attack they knew was coming, Gibbon’s attention was suddenly drawn to the “wail of mingled grief, rage, and horror which came from the camp four or five hundred yards from us when the Indians returned to it and recognized their slaughtered warriors, women and children.” Reentering the destroyed camp and seeing their dead, men and women alike were overwhelmed with grief, many falling to the ground and openly weeping for those lost. Owyeen was shocked by dead children she earlier had heard screaming in a burning tipi. “We found the bodies all burned and naked,” the woman said, “lying where they had slept or fallen before reaching the doorway.”

In a shallow ravine, Duncan McDonald reported that several women were found killed, one with the bodies of three dead children cradled in her arms. Pahit Palikt, a young boy about ten years old, wandered through the camp and, discovering dead women and children lying about, wondered why so many were asleep. Walking among the smoldering tipis, Yellow Wolf saw the bodies of soldiers and warriors, some in deathly embrace. “Wounded children screaming with pain. Women and men crying, wailing for their scattered dead! The air was heavy with sorrow. I would not want to hear, I would not want to see, again.”

Warriors lost no time stripping dead soldiers of their weapons to use on those yet alive. Yellow Wolf stopped by one man sprawled face down with a knife still gripped in his hand. “When I stooped to get the gun, the soldier almost stabbed me. His knife grazed my nose. I jumped five, maybe seven, feet getting away from that knife. Approaching, I struck him with my kopluts. He did not raise up.” The Nez Perce discovered other whites across the battlefield who were still alive. One young soldier, Francis Gallagher, listed as a “musician” on Gibbon’s roster, was shot through both lower legs. Unable to retreat with the others, he was found later with his throat “stabbed in three places.”

When volunteer Campbell Mitchell was discovered, some Nez Perce suggested questioning him; others wanted to kill him immediately. One account has Mitchell telling his interrogators that “Howard would be there in a few hours and that volunteers were coming from Virginia City to head the Indians off.” (It is unclear how the volunteer would have known this since the command had received no messages from Howard.) While the man was talking, a sobbing woman who had lost both her children and a brother in the fight, walked up and slapped Mitchell in the face. When the volunteer kicked the woman in return, a nearby warrior promptly shot him. Another account claims that Mitchell “died a more fearful death,” implying he was tortured, and years later Corporal Loynes maintained that he could plainly hear “the cries of our wounded when the Indians finished them.” But Yellow Wolf denies this happened, saying that all prisoners were quickly killed by warriors furious at what the “cowardly coyotes” had done. Whatever the truth, it appears that of the whites who fell in the initial battle, as many as seven may have been found wounded but still alive by the Nez Perce. None survived.

Unsure of the Indians’ intent, Gibbon and several officers ventured to the edge of the trees to reconnoiter in the direction of the village. Here the bench fell away sharply fifteen or twenty feet down a steep embankment to the creek and willows below. As the men watched, they could see warriors “creeping forward through the brush,” and several stood up and commenced firing. Standing next to Gibbon, Lieutenant William English suddenly “fell backward with a cry,” wounded by a sniper from behind, the bullet entering his back and lodging in his lower abdomen. The soldiers “now began to fire rapidly,” said Gibbon, “and were excitedly throwing away their ammunition.”

As the men hunkered down, some sixty warriors led by Ollokot took up positions around them. There they kept up a fierce barrage of both yelling and gunfire, forcing the soldiers to remove their hats to avoid drawing fire. Particularly vexing were several sharpshooters who positioned themselves both in and behind large trees about 150 yards away. One of these snipers wounded no less than seven men before being felled; Lieutenant Woodruff recalled his dread at hearing the “dull thud” the bullets made hitting flesh. In addition to the sniper attacks, the soldiers’ line was constantly being tested. Sergeant Edward Page was shot and killed by a mounted warrior who brazenly rode out of the willows. When he reappeared a moment later in an attempt to repeat his success, the soldier next to Page shot the warrior dead.

South of the siege area, a shallow draw led up from the creek. Whites were startled when a lone warrior on foot suddenly made a suicidal charge up the draw, nearly penetrating their line before enough guns managed to kill him. The man’s name was Pahkatos Owyeen (Five Wounds) and he had only recently learned of the death of his closest friend, Rainbow. “A man of strong feeling, strong in battle,” Ollokot’s wife Wetatonmi described him. “Never was known to cry and show tears. Rainbow lay dead where the fighting had been hard. He and Pahkatos had grown up together. Always went together when hunting buffaloes or on warpath. Had never been separated for long. He cried over his friend. Cried long. He said, ‘This sun, this time, I am going to die. My brother is killed, and I shall go with him.’”

Also killed early during the siege was Sarpsis Ilppilp, who with Wahlitits had murdered the first whites in Idaho. According to Nez Perce accounts, the warrior had taken up a position behind a boulder only a few yards from the defended line, drawing much fire after wounding or killing several soldiers. A single bullet struck him in the neck, cutting one strand of a tight-fitting wampum necklace he was wearing, his talisman against death. He was also wearing a white wolfskin cape which had special spiritual powers. At least eight warriors tried to recover the body and cape and several were wounded before one, himself shot in the attempt, finally succeeded. Injured in the back of the neck, the man’s hands reportedly shook uncontrollably for the remainder of his life.

Of the four horses taken into battle, only Lieutenant Woodruff’s reached the siege area alive, but the animal thrashed about so much from its wounds that when it began to draw fire, the men shot it. As the morning wore on, several Nez Perce positions became preferred targets for soldiers. One large boulder in particular sheltered a warrior calling on his wyakin for success, attracting considerable fire from those unnerved by his constant chanting (the rock’s bullet pockmarks are still quite visible). Between brief lulls in the fighting, men treated their wounds. Without a surgeon or medical supplies, most made bandages out of shirt tails after resorting to that dubious but time-honored frontier practice of spitting tobacco juice into their wounds. Others more desperate may have resorted to another technique: splitting a rifle cartridge, pouring black powder into the wound and striking a match, cauterizing the blood vessels to stop the bleeding.

At one point in the fight, Private Charles Alberts crawled up to Lieutenant Woodruff, exposed the wound in his left breast, and asked the lieutenant if he would live. “Knowing from the bubbles of air in the flowing blood that the shot had entered the lungs,” said Woodruff, “I told him to let me see his back, where I found the ball had come out. I described the nature of the wound and said: ‘Alberts, you have a severe wound, but there is no need of your dying if you have got the nerve to keep up your courage.’ Two years later Alberts, a hotel runner, was the first man I met in getting off a train at St. Paul [Minnesota]. He rushed up to me, grasped my hand and luggage and said, ‘You see, I had the nerve, Lieutenant.’”

Not long into the siege, the soldiers were momentarily heartened to hear the distinct sound of two shots from the howitzer. Gibbon, however, quickly realized the danger when no more rounds followed. The distant sound of gunfire and yelling soon confirmed his fears that warriors had captured both the gunnery piece and the commands’ reserve rifle ammunition. Following Gibbon’s orders to start for the fight at daybreak, six soldiers and two civilians had led mules hauling the wheeled howitzer and a horse laden with ammunition to a nearby hillside position. When they saw Indians approaching, the men managed to get off two shots before the warriors closed in. Two privates immediately fled, Gibbon saying later that “they never stopped until they had put a hundred miles between themselves and the battlefield.” One man was killed and two were wounded. Private John Bennett, riding one of the team mules, became entangled in the harness when the animal was wounded, landing underneath as it fell. Cutting himself loose and frantically prodding the dying animal with his knife, he managed to roll free and escape back down the trail along with the other survivors and eventually reached the wagon train camp.

For the warriors’ trouble, they managed to capture two thousand rounds of .45/70 caliber ammunition, usable in Springfield rifles taken from dead soldiers. Exactly what happened to the howitzer is disputed, Gibbon claiming his men hid the friction primers necessary to fire the piece before abandoning it, the Nez Perce saying they found the cannon in working order, then dismantled and hid it lest it fall back into the soldiers’ hands. The howitzer was found later at the bottom of the slope and resides today in the battlefield’s visitor center.

As Gibbon was fretting about the howitzer and ammunition, his men suddenly smelled smoke. Soon “a line of burning grass made its appearance on a hill close by, sending its stifling smoke ahead of it.” As the men prepared for a charge by the warriors, those with revolvers placed them close at hand “as a final guard against torture” should their defense be overrun. Gibbon recalled that only a year before, Looking Glass’s band had visited Fort Shaw on their return from hunting buffalo, and at the behest of “ladies at the post,” had given a “sham-fight” exhibition. Lighting a grass fire, “one side charged under the supposed cover of smoke and drove the other party from the field.” Now, with yells of these same warriors growing ever louder just behind the smoke screen, the identical technique “meant possibly defeat and death, perhaps worse.” But it was not to be. Soon the wind shifted and gradually died down, the grass fire “vanished,” and with it the threat of a charge.

By late afternoon, the shooting fell off. A quick count of remaining ammunition showed at least nine thousand rounds had been expended by Gibbon’s men since that morning. Peering through the trees, soldiers could see the Nez Perce packing up their camp and moving away from the battlefield. The injured were placed on travois or tied to horses. One volunteer judged the camp had been “badly crippled” by the number of animals he saw burdened with wounded. Still, the men feared to move. Lingering behind, their number unknown to the soldiers, some thirty Nez Perce continued to extract a toll. By nightfall an occasional shot was just enough to keep the men awake, most having slept no more than a few hours during the last two days or eaten since the previous night. One exhausted volunteer, who shared a rifle pit with twenty-year-old Tom Sherrill, managed to fall asleep lying on his back, snoring, his mouth open. Sherrill was astonished that anyone could sleep when a bullet struck nearby, filling the man’s mouth with dirt and gravel. After coughing and gasping for a few moments, he rolled over and promptly fell back asleep. Moments later, a bullet passed through Sherrill’s hat, “cutting a trail through my hair and just missing the piece of ivory in which I had been trying to carry my brains around with me for the past twenty years.”

Hunger kept some awake. Hardtack carried in their packs had dissolved when they waded the creek, and men began to eye Lieutenant Woodruff’s dead and bloated horse. Unwilling to risk a fire, some crawled to the animal and sliced strips of muscle from its haunches, eating the meat raw. Others preferred to remain hungry.

Of the 183 soldiers and volunteers who attacked the camp that morning, 7 out of 17 officers had been killed or wounded, with a total of 29 men dead and 40 wounded (two mortally), many severely, with more than one wound. Lieutenant English was in constant pain, wounded in the wrist, the scalp, the ear, and through the bowels. To quiet the pleading of the wounded for water, three men slipped down the gulch to fill canteens, volunteer Homer Coon saying that “as thirsty as I was, I actually forgot in my excitement to get a drink myself.” Throughout the night, Corporal Loynes recalled the agonizing cries of the wounded man next to him in his rifle pit, drummer Thomas Stinebaker, “moaning from pain and crying for water until he died near dawn.”

Sometime during the night, between five and seven volunteers slipped away and headed back to the Bitterroot Valley. Becoming disoriented in the dark, they eventually stumbled into Howard’s command the following day. After leaving Howard, the men apparently lost their way in the mountains, not arriving back in the settlements for almost two weeks.

Believing the attack would be renewed in the morning, Gibbon—that day marking his thirtieth year in the army—sent several messengers for help. One man carried a message for Howard that Gibbon had scribbled on a small scrap of paper, briefly describing the battle, the command’s location and the need for both “medical assistance and assistance of all kinds.” A fervent postscript read: “Hope you will hurry to our relief.” The man failed to discover Howard’s forward detachment along the back trail but did find Major Mason and the remainder of the cavalry the following evening. Without delay, the major dispatched two of the command’s surgeons to aid Gibbon.

Two other men were sent separately to Deer Lodge that night, volunteer Billy Edwards slipping through the Indian line and arriving first in what must have been an incredible journey. Alternately running and walking some forty miles, he came to a homestead and obtained a horse, then rode the remaining forty miles, arriving in Deer Lodge thirty-four hours after leaving the command. One of the messages Edwards carried was addressed to Governor Potts and implied certain defeat, describing the besieged troops and saying, “We need a doctor and everything (food, clothing, medicines and medical attendance). Send us such relief as you can.” With a telegraph office at Deer Lodge, this brief first news of the fight was wired to Helena and that same afternoon appeared in a special edition of the Helena Daily Herald.

Gibbon’s message to General Terry telegraphed that same day was just as terse, if not entirely the whole truth:

Big Hole Pass, August ninth

Surprised the Nez Perces camp here this morning, got possession of it after a hard fight in which both myself, Captain Williams and Lieuts Coolidge, Woodruff and English wounded, the last severely.

Terry passed on this message, along with the first newspaper reports to General Sheridan, who in turn telegraphed the adjutant general in Washington, D.C. All of the generals, upon hearing two seemingly disparate accounts, chose to disbelieve the published version in favor of Gibbon’s telegram, so much did they doubt the possibility of what had happened to his command. Not until the second messenger straggled into Deer Lodge with additional details were they forced to admit the newspaper had been correct.

Just after dawn on the second morning of the siege, both Indians and soldiers alike were startled when a white man suddenly appeared on horseback and charged past the warriors into safety behind the soldiers’ defenses. A moment later the Nez Perce heard loud cheering, which they understood to mean that reinforcements were coming. By now, probably less than a dozen warriors remained, most having slipped away during the night to join the fleeing camp some dozen miles to the south. Asked later why they declined to press the attack, Yellow Wolf responded that their obligation lay with their families. “If we killed one soldier, a thousand could take his place. If we lost one warrior, there was none to take his place.” In his official report, Gibbon claims the Indians continued to fire upon his men until late into the night of the second day, but Yellow Wolf later derided this, saying with probably some truth, “Afraid of armed warriors, they lay too close in dirtholes to know when we left!” Other testimony and events occurring after the arrival of the messenger lend support to Yellow Wolf’s statement that after a cursory look down the back trail that morning, these last warriors fired a “good-bye” salvo at the troops and soon left to join the bands.

The courier, a civilian sent by Howard, delivered the welcome news that the general and a relief detachment were only a day away. Gibbon became concerned, however, when the man reported he had not seen the command’s wagon train camped some five miles up the trail. Tensions eased somewhat when Sergeant Sutherland finally appeared a short time later. Stumbling on Gibbon’s wagons the day before and warned of the ongoing fight ahead, the sergeant had elected not to carry his now nearly four-day-old message to Gibbon until the following morning. The camp had been moved off the trail after the return of the howitzer fight survivors, accounting for the first messenger’s inability to find it. Not long after Sutherland arrived (unchallenged by warriors if they were present), Gibbon sent a detail to escort the wagons to the siege area. Why the Nez Perce had not found the men and wagons when they searched the back trail that morning is puzzling, although it appears they may have come close, missing them by only several hundred yards.

That the men refused to abandon the wagons in light of the Indian force they knew was only several miles away does not deny the fact that they feared attack. Lieutenant Joshua Jacobs’ servant, William Woodcock (some African-Americans continued to serve former white masters long after the Civil War ended, an accommodation the U.S. Army conveniently overlooked for officers), was put on guard duty one night with the lieutenant’s shotgun loaded with birdshot. Described as “a vigilant sentry, but a poor shot,” Woodcock is said to have mistaken the wagon master for an Indian and challenged the man and, without waiting for a reply, emptied both barrels at him. When the smoke cleared, the charge of buckshot had torn up “the ground and cut down the brush,” but the wagon master was unhurt.

When the wagons rolled in late that afternoon, the men cheered, built fires to cook salt pork, and tried to make the wounded more comfortable. Many had suffered throughout the heat of the day, the air thick with flies on the dead and wounded. One man later claimed he lost several inches of bone in his wounded arm to maggots. For the first time in nearly sixty hours, the exhausted men slept.

Since sending Sergeant Sutherland with his message for Gibbon, General Howard had moved quickly to close the gap between the two commands. When he arrived at the terminus of the Lolo Trail in the Bitterroot Valley on August 8, he learned that Colonel Wheaton’s force, commanded by Captains Perry and Whipple and due to arrive in Missoula via the Mullan Road, was so hopelessly behind that they would never effect a timely rendezvous. Thus he sent Lieutenant Harry Bailey back with a message ordering them to return to Idaho.

On the day Gibbon attacked the village, Howard’s command traveled thirty-four miles up the Bitterroot. The next morning, the general left orders for Mason to follow with the remainder of the cavalry. Taking his staff, twenty cavalrymen and seventeen Bannock scouts, Howard pushed over the pass into the Big Hole Valley, remembered by saddle sore Thomas Sutherland as a “tremendous ride” of fifty-three miles. That night the volunteers who had abandoned Gibbon walked into camp. Gibbon “has lost half his men,” they told Howard. “It was going hard with him when we left.” Howard recorded that “no offer of favor or money . . . could induce one of those brave men to go back, and guide us to the battlefield.” The general ordered additional campfires struck to give the appearance of more men in case Indian scouts were nearby. Then he dispatched a runner back down the trail to tell Mason to bring up the troops.

The next day, Howard and his party of about forty men rode into Gibbon’s camp. The camp appeared more like a hospital than a fortification, said Howard. Near one corner “reclined the wounded commander. His face was very bright, and his voice had a cheery ring as he called out, ‘Hallo, Howard! Glad to see you!’”

There was little anyone could do until morning when Surgeon John FitzGerald and another doctor arrived and began ministering to the wounded. A few hours later, Major Mason and the remainder of the cavalry finally caught up. Although Gibbon would soon report that there was but one man “who could have been benefited by the presence of a surgeon with our command,” FitzGerald wrote to Emily that upon reaching the camp, “we found a horrible state of affairs. There were 39 [actually 40] wounded men without Surgeons or dressings, and many of them suffering intensely.” FitzGerald also observed that had not the messenger arrived alerting the remaining warriors that help was rapidly approaching, “I think it probable they would have finally annihilated them. As it was, he [Gibbon] ‘stood them off’ for two days, when all but a few warriors left.” Such was hardly the case if Nez Perce sources are to be believed, but this conviction undoubtedly gave FitzGerald and others of Howard’s command satisfaction that their arduous journey had not been in vain.

That day the survivors set about burying their twenty-nine dead—two officers, twenty-one enlisted men, five civilian volunteers, and one army scout. At the same time, the Bannock scouts began to disinter the Nez Perce dead (apparently without objection from Howard), scalping and mutilating the bodies. Tom Sherrill watched as they first scalped one dead warrior, then “kicked him in the face, and jumped on his body and stamped him. In fact they did everything mean to him that they could.”

When it came to an accurate count of the exposed bodies, virtually no two white reports agree. With the exception of warriors who fell too close to the soldiers’ defenses, all corpses had been buried by the bands before leaving the battlefield, for the Nez Perce believed that burial was highly desirable before passage was possible to a spiritual hereafter. Although some graves were concealed, most had been hastily dug and were shallow. Many of the bodies were wrapped in buffalo robes. Several had been laid in a row under an eroded creek bank, and then the bank collapsed, the earth barely covering the corpses. When the Bannocks were done, Amos Buck, brother of Henry and a participant in the fight, counted sixty-seven bodies, although he noted that additional corpses he had not seen were reported downstream of the battlefield. Howard claimed his men reburied the exhumed dead, but ill-equipped for digging, the effort was at best superficial.

Gibbon officially reported eighty-three dead Nez Perce were found, with six additional bodies located later in a nearby ravine. Some said more had died, one white source claiming 116 corpses and another as many as 208. A few days after the battle, Surgeon FitzGerald wrote to Emily that he had seen “30 dead bodies (mostly women and children).” FitzGerald went on to disparage Gibbon’s official denial of harming women and children who had taken shelter in the creek and willows after the initial charge. “I was told by one of General Gibbon’s officers that the squaws were not shot at until two officers were wounded by them, and a soldier or two killed. Then the men shot every Indian they caught sight of—men, women, and children.”

Almost as conflicting are Nez Perce accounts of the number dead. Wounded Head claimed sixty-three died (ten women, twenty-one children, and thirty-two men). After interviewing survivors in Canada the following year, Duncan McDonald reported seventy-eight dead, of whom thirty were warriors. Closer to this estimate, Chief Joseph put the number at eighty—thirty warriors and some fifty women and children.

Some of these inconsistencies may be attributed to the confusion immediately following the fight, as the bands quickly buried their dead and fled the battlefield. Several youths seeking shelter from the fight became separated from the bands and made their way back to Idaho and eventual imprisonment, thus avoiding an after-battle head count. Also, the wounded who subsequently expired along the trail may not have been tallied among those who died on the battlefield. Whatever the actual number, most authorities believe between seventy and ninety Nez Perce died as a result of the battle, of whom probably no more than thirty-three were warriors.

Perhaps more revealing than body counts is how whites viewed the attack. It was “the most gallant Indian fight of modern times,” acclaimed the Missoulian, one that will forever “cause a thrill of pride to every Montanian.” From his headquarters in Minnesota and anxious to regain lost ground after his deplumation the summer before, General Terry proclaimed Gibbon’s effort a “brilliant success.” Expressing “feelings of great admiration” for those soldiers and volunteers who waged the battle, Terry sidestepped any discussion of Gibbon’s methods, seizing the opportunity to blame congressionally mandated troop reductions resulting in an army so emasculated that its “distinguished” commander had to fight “rifle in hand” like a common private. Certainly Gibbon’s actions did not hurt his chance for promotion; he went on to serve as commander of the departments of Columbia and California.

In a statement released three days after the fight, Terry’s superior, Phil Sheridan, sounded only moderately less upbeat, terming the battle a “substantial success.” Interviewed later by a gadfly New York Herald reporter who questioned the army’s optimism about a battle that seemed more like a defeat, the general became apoplectic. If Gibbon appeared overeager, it was only because his command under Rawn had been roundly accused of “cowardice” a week earlier for not attacking with even fewer men. Now newspapers were calling Gibbon “a fool for venturing to put 150 men against four times that number of Indians,” huffed Little Phil.

Any rationalization about a battle that had left so many women and children dead is conspicuously absent from official reports. Every surviving officer received a brevet recommendation, and seven enlisted men eventually received the Medal of Honor, one purportedly responsible for the deaths of nine women and children. There seems little doubt that no officer felt compelled to address this issue since Sherman himself had defended war against noncombatants time and again, claiming that in the end it is more humane because it speedily ends resistance. Only eleven years before, after Wyoming’s Fetterman Massacre, it was Sherman who had written Grant a widely circulated letter declaring that “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children.”

Writing in one of his many published accounts after the war, Howard defended Gibbon’s actions. Of course he was “horror-stricken” upon seeing the bodies of women and children, but outrages committed by Indians against whites “are a thousand times worse.” When it came to accounting for the deaths of children, volunteer John Catlin wavered not at all. In words that might have fallen from the lips of men in past centuries as well as those to come, Catlin steadfastly maintained, “They were there with their fathers and mothers . . . violating the laws of our land and we as soldiers were ordered to fire, and we did.”

Others were less certain. Eighteen years after the battle, Gibbon—now near the end of his life—harbored that disturbingly paradoxical attitude expressed by more than a few soldiers who served on the frontier long after the last official shot had been fired at an Indian: that soldiers had been nothing more than reluctant instruments in carrying out government policies. Defending their personal actions, they lamented what those actions ultimately accomplished. Killing women and children at the Big Hole had been “unavoidable,” said Gibbon. In almost the same breath, he admitted that the war against the Nez Perce was a “cruel fate” marking “the culminating point of the maltreatment of the Indians in this country.”

Some of those lower in the chain of command were even more uneasy. After viewing the exhumed bodies, Major Mason wrote to his wife that “it was a dreadful sight—dead men, women and children. More squaws were killed than men. I have never been in a fight where women were killed, and I hope never to be.” And Corporal Loynes, writing Lucullus Virgil McWhorter over half a century after the battle, revealed that “in the few living members of my regiment whom I receive letters from, they have mentioned with regret that it was their duty to attack those people.” One can only imagine how Stevensville merchant Henry Buck, temporarily conscripted as a teamster for Howard’s command, must have felt when after the battle he stumbled on the partially exposed body of a woman, recognizing “the calico dress that she wore as being made from cloth that I had sold her only a few days before.”

In coming weeks, curious citizens would travel to the high, wind-swept valley to view the battlefield, one journalist remarking that the odious sight of “festering, half putrid corpses” of the scalped and mutilated Indians was the most “horrible and sickening I ever beheld.” Anticipating exactly what had happened, several Nez Perce managed to return in the first few days and under cover of darkness rebury some of their dead. Soon, however, white grave robbers exhumed the bodies yet again, searching for Indian souvenirs and artifacts. One party from Deer Lodge reported finding fresh dirt and a tuft of buffalo robe protruding from the ground. They attached a lariat to the robe and took a turn around a saddle horn, and up came several bodies.

In late September, Captain Rawn sent a burial detail to the battlefield after receiving reports that bears had come down out of the mountains and dragged several corpses to the surface. The men reinterred the whites, counted more than eighty exposed Indian bodies, but made no attempt to rebury them.

One year after the battle, fur trader Andrew Garcia and his Nez Perce wife, In-who-lise, who had been shot in the shoulder, had her mouth smashed with the butt of a soldier’s rifle, and lost her sister and father during the battle, returned to the Big Hole to locate and bury their remains. Garcia found “human bones and leering skulls” of Indians scattered throughout the tall bunchgrass and among willows near the creek, while nearby white graves appeared undisturbed. Late that evening, as dusk crept across a blood-red western sky, In-who-lise began wailing for the dead, a sound so eerie and mournful that Garcia would never forget it.

“You can hear it a long way,” said the frontiersman, “and it haunts you for days. As her piercing wails came and went, far and near through this beautiful still valley of death, they would come echoing back in a way that made me shiver, as though in answer to her sad appeals.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.